Coming Clean

The Laundromat was packed. I stuffed my clothes into an oversized washer, added detergent and pushed in a dozen quarters. Seeking relative calm, I settled into a plastic orange chair next to a table piled with clean clothes where a very pale young woman and a wiry young man were folding.

“Isn’t it amazing what you can figure out from someone else’s laundry?” she asked, handing him the button that had just popped off one of his shirts. He blushed, pushed the ragged athletic sock he was holding back into his pile. She grinned kindly.

They had just met.

“I mean, take my slippers; they say oceans about me,” she bragged, presenting an otherwise unrecognizable handful of purple rags. He smiled, and visibly exhaled. Clearly relieved that she wasn’t judging him, he reached back in for his sock.

I listened in on their conversation while flipping through an old copy of The New Yorker. They were unusually forthcoming with one another about their lives, perhaps because folding one’s underwear in front of a stranger is revealing. He told her about his recent divorce.

“She had an affair and then kicked me out of the house,” he said, dismissing his marriage with a tired shrug. “I don’t have any illusions or regrets about her, but…” His voice softened. “My daughter just turned three, and it kills me that she’s facing this now…” He swallowed hard. “I see kids whose parents are divorced. They go to separate dinners on Thanksgiving, and they carry bigger backpacks with the clothes they’ll need for a weekend with the other parent.”

She listened without judgment, nodding, offering no solutions.

He took a deep breath. “I tried to salvage the marriage for my daughter, but I know that would be even more damaging. When my wife and I were screaming at each other, she’d come over to us and reach up for our hands, trying to pull us together.” His voice broke. “This was before she could even really speak in sentences.”

He paused, and I quickly glanced up from my magazine to see him lower his chin and bring a fist to his mouth as he cleared his throat.

There was a pause. She took a deep breath, and then told him that she was recently diagnosed with leukemia, and that she faced a grim prognosis. He put down the shirt he was folding, and stared at her in alarm.

“They tell me that I’m looking at about eighteen months. But…,” and here her eyes danced, “they don’t know the trick I’ve got up my sleeve.” She leaned toward him conspiratorially.

“I got plans!”

His face lit up, a mirror of hers; their eyes in silent communion. I was staring at them now, but I might as well have been invisible. Their faces were locked in an exchange of raw emotion.

She told him that she wanted to ride a motorcycle through the Swiss and Italian Alps, and how she planned to take a rafting trip on the Colorado River near the Grand Canyon. He listened, rapt, staring at her in awe. I leaned in.

She described a hot air balloon festival in New Mexico, hundreds of brightly colored balloons inflating each morning. She talked about going to the summit of Haleakala on the island of Maui to view the rings of Saturn through a telescope at night. He stopped folding altogether. I held my breath, hanging on her words.

When she finished explaining that she needed a pilot’s license and planned to fly a single-engine plane, I exhaled. He finally stopped her.

“So, what are you going to do first?”

The young woman raised her eyebrows in surprise. “Excuse me?”

“All these plans, when are you going to get started?”

“Oh.” Her face lost the color that it had briefly gained. “Well, I’m currently receiving weekly blood transfusions, and I get daily injections to boost my neutrophils. I’m scheduled for another bone marrow biopsy this summer. But at some point, if my doctors say that I don’t need transfusions as often…” Her voice trailed off.

“Don’t do that!” He startled her with his tone.

“Do what?” She seemed momentarily lost.

“Don’t go there! I just met you, and I can already see what you’re doing. You can see the way out; you know how to take yourself away from all this,” as he gestured to himself and the laundromat, “and then you let yourself get pulled back into hopelessness. The disease has planted that despair! It's terrible what you're facing, but you can beat this!”

“But,” she hesitated, choosing her words with care. “I don't think this battle is about strength. I feel like I’m trying to adapt my swing to a curveball. This is a game I’ve never played before, and one that I don’t fully understand.”

“Okay,” he countered, following her analogy, “but the coach says you’re on the roster, so get up there with your bat in hand, and do what you can. Don’t resign yourself to expectations! You need to remember what you just told me – you got plans!”

“Damn straight!” My voice shocked all of us. They turned and stared at me. Tears ran down my face. I looked directly at the woman, wiped my nose, and pointed at the young man.

“What he said.”

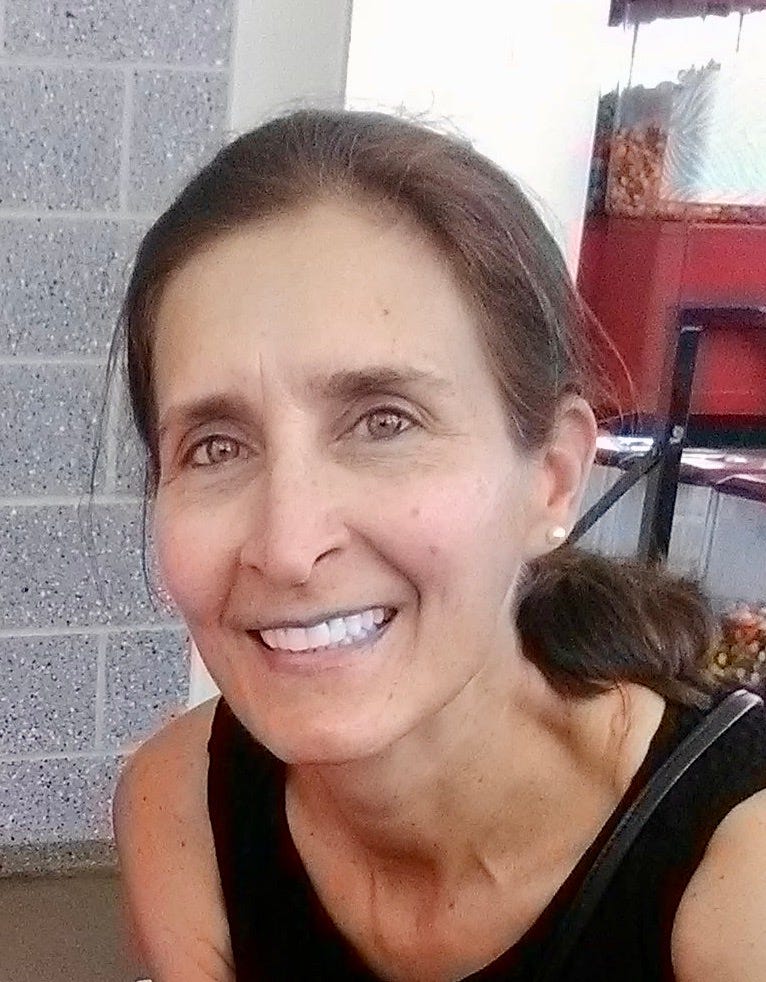

About the Author

Elizabeth Castronovo has lived with cancer for 22 years. Through tears, laughter, and writing, she clings to the thread of sanity. She maintains a daily sense of awe while taking long walks around the lakes with her dog. She lives in Minneapolis with her family.