My world is richer because I know Dina Friedman. She is a font of inspiration with prodigious creativity, productivity, and skill. She provides wisdom and a calming presence whether she is convening our local cultural council, speaking as a voice of reason at town meeting, or rolling out her yoga mat around the pond at Andrews Greenhouse.

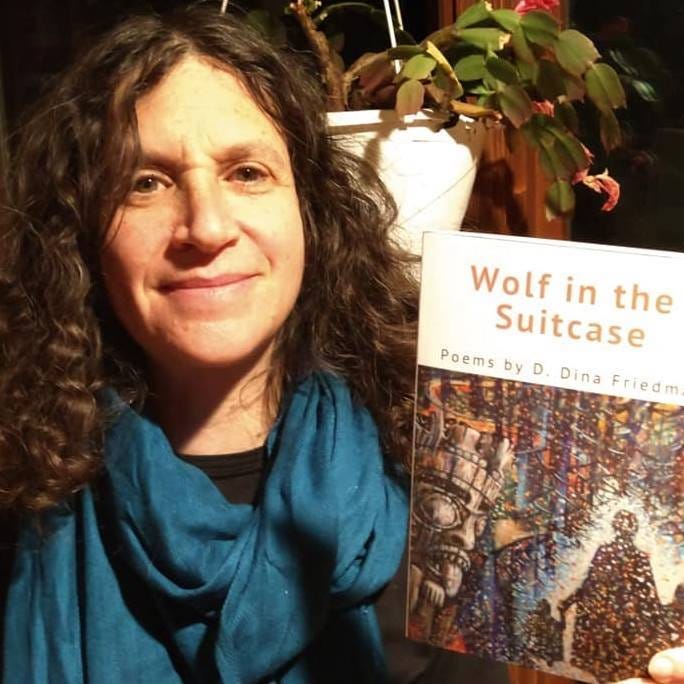

I am happy to facilitate your acquaintance with this amazing writer who has published two young adult novels (Escaping into the Night) and Playing Dad’s Song), a chapbook of poems (Wolf in the Suitcase), and a short story collection (Immigrants). Her second book of poems, Here in Sanctuary-Whirling, will be released this spring.

Dina has also published poetry and short fiction in more than 100 literary journals including Rattle, The Sun, Mass Poetry, Chautauqua Journal, Crab Orchard Review, Cider Press Review, Hawaii Pacific Review, Cold Mountain Review, Lilith, Negative Capability and Rhino, and received four Pushcart Prize nominations.

“The hardest thing about writing,” Dina says, “is to keep going and believe in yourself.” Her Substack publication (Music and Musings) provides inspiration and encouragement for anyone with realized or unrealized creative aspirations--musicians, visual artists, writers, dancers, actors, and others whose struggles with perfectionism and related trauma have diverted them from their “true north.”

Dina grew up in New York City and moved to western Massachusetts in her early twenties. She raised her family and continues to live in an old farmhouse next door to a dairy farm with six hundred cows. Now retired from teaching business communication at UMASS-Amherst, Dina devotes more time to writing and community work. She is a life-long activist for peace in the Middle East, local land conservation, anti-poverty, and immigration justice. She also writes calls to action for the Substack site, Rogan’s List.

In 2019 and 2020 Dina traveled to Homestead, Florida and Brownsville, Texas/Matamoros, Mexico, where she co-facilitated writing workshops and witnessed first-hand the risks and hardships encountered by people hoping for a better life in America. “Every immigrant has a personal story,” says Dina whose new collection of short fiction shows the very personal, human side of those looking for a better life in America.

For those local to Western Massachusetts, Dina will be reading from IMMIGRANTS at the Odyssey Bookshop on Tuesday January 23rd at 7 pm. The event is free, but the Odyssey appreciates pre-registration. I hope to see you there.

When she’s not writing, doing political work, or spending time with friends and family, Dina enjoys cooking, making music, hiking, gardening, and traveling.

Read on for excerpts of Dina’s work and an interview about her creative process.

Excerpt from The Bridge, a story in IMMIGRANTS

“Go,” the mother repeats, dropping coins into the slot by the turnstile—what the girl heard her call her “lucky pesos.” From there, the girl will have to walk to the middle of the bridge alone, where the U.S. border station is located.

“No, Mama!” The girl feels a sick sensation in her stomach, worse than the days they had no food. She and her mother have talked about this moment, how she needs to be a big girl. But the bridge is much bigger than she is, and the only safe place she’s known since the bad men has been in her mother’s arms.

The mother bends down and puts her hand on the girl’s shoulders. “Don’t be afraid. You’re not alone. God is with you.”

The girl looks around for God. She’s never understood why people, even grown-ups, believe in invisible things. She prefers the reality of what she can see and feel, like the soap in the squirt bottle that will keep your hands clean and prevent you from getting sick. She already knows she wants to be a scientist when she grows up. She spends hours every day with Joaquin on the muddy riverbank pulling up weedy grasses to add to her collection.

The mother leans over and kisses the girl one more time on the cheek. “Go.” She pushes the girl through the turnstile.

The metal bar comes all the way up to the girl’s neck. It’s cold enough to make her shiver and the girl wonders whether this is what the hielera will feel like. All the children talk about the hielera, which is where they put you if they catch you crossing over. Cold, like a refrigerator, the children say. Cold, like snow. None of the children have ever seen snow, which is something only to be imagined, like God. The girl doesn’t want to go to the hielera. Why is her mother making her go across the bridge? Does her mother not love her anymore? Did she do something bad? Maybe her mother is crazy, like Katrina’s mother, who had to go to the hospital and didn’t come back.

The girl walks a few steps, then turns and sees the back of her mother running toward the splay of muddy tents. So, she keeps on going, not because she wants to, but because she knows her mother wants her to. Up in the sky, she looks for God. All she sees is fog.

Here in Scantuary—Whirling (Querenica Press, 2024)

Dina’s new collection of poetry, Here in Sanctuary—Whirling, (Querencia Press, 2024) also draws on her years of immigration justice activism. Poet Rich Michelson claims, “Whatever else it may be, poetry is foremost a witnessing, and D. Dina Friedman is our conscience and guide as she transports us to the border –physically and poetically—so we can better understand the pain and struggle that keeps the machinery of the world running, and what drives a person to become so desperate that he might send his daughter over the bridge alone to face the guards. How is it that we have become people who love each other/hating the people across the river, who love each other?”

I Do Not Know

Why the wind is so fierce today. Why some people die and others recover. Does a tornado choose its targets? Is there a blueprint somewhere with the secret path of my life mapped out? Will this trail I’m on connect with the ridgeline, or will it keep crossing the same stream? How do I get to the bunker, and what’s hidden there now that the army no longer has it? I do not know how dirt feels to a carrot root, or to my brother six feet under. Is he able to read the prayer books placed on his coffin through some double miracle of semi-resurrection and dyslexia cured? What does it feel like to a dyslexic when letters leave their prescribed places? Why do bodies compartmentalize into people who love each other hating the people across the river, who love each other and hate the people across the river? Why do we have to teach toddlers to share sand-buckets? Why don’t they do it naturally? Why don’t we do it naturally? Why don’t we do it?

You can hear Dina read more of her poems on Jazz Ready.

Dina is also the author of a not-yet published memoir, Imperfect Pitch, about her journey to reclaim herself as a flawed musician in a multi-generational family of music professionals. She explores the memoir’s bigger questions about the innate human drive for creativity and the obstacles our society throws in its way in her blog Music and Musings: Living a Creative Life in a Creatively Challenged Universe.

Excerpt from Imperfect Pitch: A Memoir About Passion, Piano, and Perfectionism

I don’t know how my grandfather Arthur became “San Francisco’s violin genius,” as the vaudeville style poster from 1921 advertised his first solo concert at age 17. I didn’t witness the first time he put bow to string and played his first baby song or any other part of the long, difficult journey he took before becoming recognized for his playing, so I don’t know how he learned to sink into sound and make it matter. I do know that later he played in symphonies for famous conductors, like Ormandy and Antonini, and that he didn’t let himself be subsumed by the wow factor of these famous names or their acclaim in the musical hierarchy. And I also know that during World War II, he came home from his job at the CBS Symphony one day and said he couldn’t play anymore because the conductor was using the music to send secret codes to the Nazis.

“Lie down, Arthur.” My grandmother heated a handkerchief and knotted it around his head. She rubbed between his brows until he slept: all evening, and the following morning, and days after, when he didn’t go to work—love for his country trumping food on the table.

Eventually, he got a job selling houses. He said to my grandmother, “Don’t buy a house in a gully. The run-off will flood the basement. Buy a house on a hill. It’s better.”

The symphony was on the radio. “Don’t listen,” he said. “The Nazis. The secret codes.”

“Lie down, Arthur,” she said.

He didn’t lie down. He picked up his violin and went to practice a concerto, hearing the stern voice of Tchaikovsky saying, “no.” There was never a time when Tchaikovsky said, “yes.” At best, Tchaikovsky was silent.

“Which way is better?” He continued to ask my grandmother, as he played the passage twice: first with an accent on the hill, then with an accent in the gully.

My grandmother sighed again. “They’re both beautiful, Arthur.”

My Interview with Dina Friedman

When did you start writing and what inspired you?

I think I was around 8 when I decided I wanted to be a writer—probably because even then I had doubts that I could be what I really wanted to be, which was a Broadway musical theatre star or a Carnegie Hall caliber pianist. But, unlike those careers, writing didn’t depend on other people’s applause for immediate validation. I could write privately, and rewrite as much as I wanted to until I was satisfied.

How did you grow into your identity as a writer?

This is a great question! As much as I made a priority to devote time to writing, even when I had a stressful day job and was raising two kids, there were many points in my life where it was very hard to say, I am a writer. It was much easier to identify myself by stating what I did for work. It helped to be part of a number of different communities over the years—various workshops and critique groups—where we could remind each other of the importance of identifying as writers, regardless of how much we had published. As my late mentor, Pat Schneider, founder of Amherst Writers & Artists used to say, a writer is someone who writes. Even after I published my first book, Escaping Into the Night, with a major publisher in 2006, it still felt hard to say I was a writer, because now I had to measure myself against a different level of success—how well my books were selling. I think it’s only in the last few years (and four books later) that I’ve really been able to claim the identity—perhaps because I’m now retired and writing is what I spend the bulk of my day doing.

How has your work changed over the years?

For better or for worse, one thing I do when I feel I’ve hit a writing impasse is to switch up the genre. In my teen years and early twenties, I wrote mostly poetry, and maybe a few short stories. Then I decided to try writing novels and wrote three unpublished adult ones before trying a YA book, which was the one that ultimately got published. I got one more children’s book (middle grade) published, and then wrote five more MG/YA novels that didn’t get published before going back to try another adult novel—also currently not published. Then I went back to writing poetry—which I’d never given up, I just hadn’t focused that much on it—and started getting serious about publishing that, which led to my two chapbooks. I also started a bunch of new short stories, most of which ended up in Immigrants, and wrote a memoir about my family’s music heritage and all the baggage it brought, which I’m still shopping around.

I think my work in all the genres deepened as I learned more craft and also since I made a decision to be more authentic in telling hard truths. Even when writing fiction, the plots and characters are made up, but underneath there is truth that matters deeply to me.

What are you reading or listening to these days?

At the moment I’m reading Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead and listening to The Buddha in the Attic by Julie Otsuka. I’m also reading a poetry collection by Pamela Wax called Walking the Labyrinth. I try to read poetry as well as fiction every day, and with poetry I’ve found that I do better with it if I don’t rush through, but instead just savor 1-3 poems every day.

What do you do when you are stuck?

When I’m stuck, I often submit work. This gets me into small revisions, which gets me into a headspace where I’m thinking about my work rather than whatever it is that got me stuck, and usually after that, I can get into a bigger project. If I can’t (and it’s not winter time) I go into the garden and weed. I get my best ideas when I’m weeding.

How often do you write? Do you have rituals or routines?

I try to do something writing-related every day, but life happens and I don’t sweat it if I don’t write. I generally don’t write when I’m on vacation, or even on day-cation, or have house guests, unless the guests are out doing something else. It works best for me to write in the morning after exercise and breakfast, but I’m training myself to write in the afternoons as well, especially in the summer when I want to garden in the morning before it gets too hot. I don’t really have heavy-duty rituals or routines, but I will often start a session by allowing myself a few minutes of procrastination playing Wordle or doing Duolingo, just to make the transition to writing less intense.

What is your process for creating and completing a new work?

I don’t have a particular process. Each work is different. A poem is a lot less formidable than a novel, for example. And many of my poems-in-progress get abandoned. With longer prose projects, I try to write 2 pages at a sitting, and while I’ll read over what I’ve written and make minor corrections, I try not to get caught up in major editing until I’ve written a whole rough draft. Then I’ll give the project a few weeks off between each draft before reading it over so I can approach it with a fresh eye. I generally don’t give things to critique groups or beta readers until I’ve revised a few times. At that point, I’m usually more frustrated than in love with the work and I can take feedback more objectively, and also know intuitively which feedback is useful to where I want to go and which isn’t. I generally don’t outline or do much planning ahead, which means I surprise myself as I write, though I also take a lot of wrong turns that I need to cut out later. In later draft stages, when the structure, characters, plot, and setting are clear, I read aloud to myself to focus on language and cutting out chaff.

What’s the best advice writing advice you’ve received?

--No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader—Robert Frost

--If you’re slogging away at your draft and something occurs to you to write that you think is incredibly stupid, cliché, etc., write it down anyway, because that will bring you to the gem that you really want to write. After that you can delete the part you don’t like. If you censor yourself, you’ll never get there.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

See above. Also just do it. Trust yourself and your process. You have the right to be creative. It isn’t magic, it’s simply letting your inner self speak and then learning some tools to make those words shine.

To learn more about D. Dina Friedman, visit her website.

Are you a creative person?

Writer, poet, artist, videographer, muscian, photographer, scupltor, painter?

I’d love to feature you in a future issue of Starry Starry Kite?