Elizabeth Castronovo 1962-2022

My sister Elizabeth was diagnosed with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) in August 2000, two months after her 38th birthday. Married and divorced twice by then, she packed more into her first 38 years than most people experience in lifetimes. A few live-in boyfriends came and went while she worked in corporate publishing and marketing. She got a master’s degree in International Business, learned Mandarin, maintained her French, and traveled. She soaked up life with every cell. She rode and raced motorcycles, taught yoga, personal fitness, and motorcycle safety, and regularly exceeded 100 mph on just two wheels. “It feels like flying,” she told me. Beth was also an exceptional snowboarder, absolutely at ease on the board, no slope too steep or bumpy. She spent a year bicycling across the country and through Europe and then another four months exploring Hawaii before she left the DC area and moved to Minneapolis, a city carefully researched (among several options) for its affordable quality of life.

When her first round of chemo resulted in a stable remission, she made plans to relocate again. This time to the Pacific Northwest. “I’ve got plans,” she told Joe when they met folding laundry in a neighborhood laundromat the day before she was to leave.

Beth never made it to Eugene. She and Joe made a life and home in Minneapolis. Olivia was born a few years later and became the most compelling reason to stay on the planet.

Beth devoted herself to mothering. Olivia never doubted that she was loved unconditionally. “To the moon and back,” Beth wrote in notes and cards. She loved the rest of us. In all ways she was a devoted sister, friend, wife, and colleague. But Olivia was her sun and moon and stars, the whole universe enclosed into one compact human being. “I love you beyond all reasonable measure,” she wrote more than once. Beth lived and loved fiercely.

Olivia graduated high school in June 2022, and Beth planned her graduation party to coincide with her birthday. “I can’t think of a better way to celebrate my sixtieth,” she told me on the phone.

A year before she had been too sick to travel with Olivia on a planned spring break tour of colleges on the east coast. I got the call, a true gift, and Olivia and I spent a week driving from Boston to Philadelphia and back again. We visited with current students and guided ourselves (because of COVID restrictions) through campuses large and small. Northeastern won her heart from the beginning. When she was accepted and awarded a generous scholarship, Beth was as excited as Olivia.

“She got into her dream school,” Beth beamed. “I am over the moon for her. She is so ready.” In late June, she and Olivia flew to Boston for orientation weekend. Olivia felt at home in her new city, ready to launch into the world.

Back home in Minneapolis, Beth fell in early July. “I was being stupid,” she told me. “Up on a stool organizing a top shelf.” A trip to the emergency room confirmed no broken bones, but the CLL was back.

When her first remission ended in 2006, an oncologist told her, “You can live to be a very old woman if you fight this cancer off six years at a time. What we used to attack with cannon balls, we now target with laser beams.” Still the treatment regimen to trigger another remission was tricky and fraught with the danger of infection. “CLL probably won’t kill you,” one doctor told her, “but a cold might take you out.”

Years of relative health were punctuated with hospitalizations, nausea, and unbearable discomfort. She never once complained. “I’m so lucky to have the kind of leukemia that mostly affects old white men,” she laughed. “Because there is so much money going into research!” She celebrated new drugs that tapped the CLL back into dormancy with fewer side effects. She became a student of her blood cancer, spoke with her doctors and nurses like a colleague.

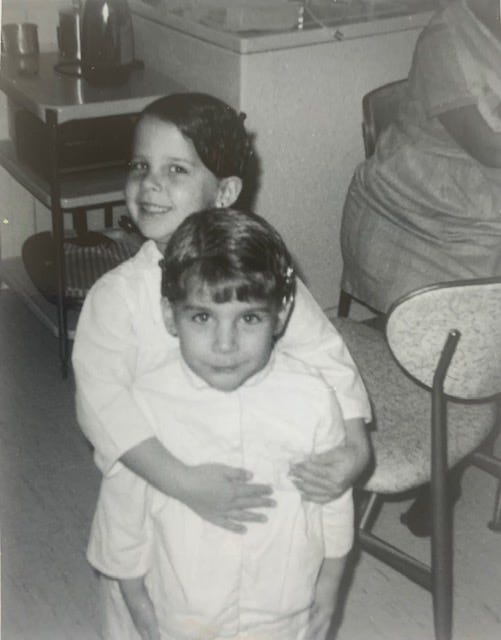

Beth was organized and tidy, some might say meticulous. Even as a kid, her side of the dresser held just a few precious things: a glass angel, a ceramic bird, a picture of her closest friend. Her side of the nightstand between our twin beds held only a neat stack of books. Even then she loved a library and was never once past due. She didn’t have to be told to get her affairs in order. Beth’s affairs were always in order, not one detail out of place.

She muscled through July and August in excruciating pain. “My sciatica is acting up,” she told us, and we let ourselves believe it was a simple orthopedic issue. “Remember the pain of my broken pelvis?” She recalled a fall in 2011 that resulted in multiple fractures and shoulder reconstruction. All movement was torturous, but she slowly rebuilt her bones and her strength. “That was a bee sting compared to this,” she said.

Still, she threw Joe a surprise 58th birthday celebration and traveled cross country for Olivia’s college drop-off. We got four days together in late August. She was frail and as weak as I had ever seen her, still in a great deal of pain, but determined to execute the college send-off she had planned.

We played games, worked a one-thousand-piece puzzle, and ate delicious meals together. She moved slowly, carefully. “I want to walk in the woods with you before we leave,” she told me. We had spent hours on the phone over the years. We talked several times a week, often while I was hiking with a dog or two on the small mountain range nearby. “I’m taking every step for you,” I told her while she was getting an infusion, resting with her legs elevated, or visualizing the chemo destroying cancer cells. ”I’m sending you love and light and healing energy.”

“I’m going to get better so I can walk in those woods with you,” she said.

“You’ll get back to those long walks around Lake Harriet,” I told her.

And she did, over and over. “I walked around the block today,” she laughed. And soon enough she was back to four miles and then seven. She bounced back from the brink so many times, it was easy to take for granted.

We took a slow walk with Olivia around the ponds the morning before she and Joe drove her into Boston. It was a stellar fall day, cool and bright, with just a hint of color to come. The trees reflected perfectly in the water’s surface. We paused a lot, breathed the fresh air. We walked arm in arm. “I’m walking in your woods,” she said, always ready to delight in small miracles.

She glowed with pleasure when they returned from Boston and relayed the details of the move-in, meeting Olivia’s roommate and her parents. She and Joe left early the next morning to make the drive back home in three shorter legs. She promised to look into transitional care to rebuild her strength.

She consulted with her doctors, talked about timing the switch to a new treatment regimen. The imbruvica had been a god-send, but this seven-year remission was clearly over. Then, on Saturday, September 10th, she woke up very short of breath with a low blood oxygen. A trip to the ER confirmed fluid in her lungs and a fractured sacrum. She was admitted to get her pain under control and begin the chemo transition.

Throughout the pandemic, Beth, I, and our brothers Zoomed most Sunday afternoons. We had our regular sibling zoom call the next day. Beth kept her camera off. “I’m here,” she said between short breaths. “The pain is better, but I don’t look so good.”

Joe spent every day that week with her and kept us up to date: visits from her medical team, two days of drug transition, the new drug, attempts to keep her fever under control, the CLL responding, the worrisome delusions. She rarely picked up when I called, but I left messages, sent her energy. Then, through Joe’s phone, I guided meditations and visualizations to breathe deeply, relax into gravity, picture the medicine doing its work, her body restored to health. She sighed in response.

“She can hear you,” he said. “She’s wiggling her fingers and toes. Her face is more relaxed.”

But the next morning, she was less responsive and her breathing was labored and noisy.

The death rattle.

She had agreed to temporary intubation, and we booked our flights.

Two at a time, we had just a few minutes each to see her before the family meeting with the medical team. She lay in complete stillness, her head turned away from the door and toward the ventilator. When it was my turn, I walked around the bed and held her hand, cold and puffy with fluid. Her eyes were slightly opened, filmy with ointment, and perfectly still.

“She’ll be sedated,” Joe had warned us. “but she’ll hear you.”

“Hi Beth,” I said. We’re here. Paul took her other hand. “We’re here, Beth.” Her head moved slightly at the sound of his voice, a twitch really, but the ventilator tube kept her turned away.

She did hear us. Some part of her knew we were there. I imagined her from the inside, the sheer force of will to acknowledge our beloved baby brother.

The machine clicked and whirred. Her chest rose and fell. Her mouth open around the tube.

Peter took Paul’s place a few minutes later. She twitched again at the sound of his voice. She loved us through the fog of sedation. She was in there. But her eyes were fixed, pupils dilated and unmoving.

Four stainless steel poles stood sentry beside the bed, dripping medicine and fluids through ten thin tubes into veins in her arms and legs. The machines and medicines kept her body alive so we could get there. She had made it. Olivia had made it to her side.

Now it was time to say good-bye.

Beth wasn’t afraid to die. We had spoken about it many times. We might lose access to our bodies, but our essence continues on in a different form. A year earlier when she was hospitalized with Covid, and it looked like she might not make it, she told me our Auntie Anne and Paul Sampley had visited her overnight.

“No matter what happens,” she said, “I’m going to be ok. We just return to the stars. It’ll be beautiful.”

“OK,” I’d said. “But all the same, I’d like you to stay in your body a bit longer.”

“Believe me,” she said. “I’m giving it my best shot.”

We had the whole afternoon before the end of visiting hours. We got to spend time with her two at a time. We reminisced about sibling vacations at the lake house, to Lisbon, to Aspen, trips to Sedona and San Diego. We told stories from childhood: biking around Preston Circle, camping trips, swimming in the pond in Oklahoma, the sandstone art gallery, building the house in Charlemont. We laughed, we cried, we held her hands, massaged her feet, rubbed her head with essential oils.

At one point, Olivia and I were with her when a young nurse came in and stood beside Olivia. “I’m Nicky,” she smiled. Colorful sleeve tattoos showed under her scrubs, her hair pulled back into a pony tail to reveal more tattoos on her neck and multiple piercings. Her tone was respectful, but also breezy and confident. “I’m covering for Amanda while she takes a lunch break. I’m just meeting your mom now, but she sounds like an amazing woman. Twenty-two years with leukemia. That isn’t nothing.”

“She is amazing,” I said. We told her about snowboarding, her love of travel, racing motorcycles. “No one ever met her who didn’t fall in love with her,” I said. “And she loved everyone in return.”

Nicky turned her attention to Olivia. “I lost my mom at a young age. She was just 62. It was the hardest thing that ever happened to me. This will be the hardest thing that ever happens to you. The only thing bad about having an amazing mom is that it hurts so much more when you lose her.”

Nicky stayed another ten or fifteen minutes. I listened as she counseled Olivia. “You’ll be angry with her at times. You’ll be sadder than you’ve ever been. Believe me, it doesn’t get worse than this. You’ll be mad at your dad, too at times. He has his own grief to process and it will be the same and different from yours. He’ll be needy and annoying, and you’ll both feel devastated, but it gets better. Believe me. It’s not a linear path, and it hurts forever, but you’ll be okay. This is as dark as it gets.”

Nicky was a virtual stranger, yet it felt like a visit from a trusted family friend.

“I have to go cover for another nurse,” she said. “But I’m glad I got to meet you and your mom.”

“Thanks for talking with me.” Olivia turned toward Nicky. “Is it okay to give you a hug?”

They held each other for a long slow breath. “Remember, you’re gonna be okay,” Nicky looked back as she headed out of the room.

Olivia watched her leave and took a another deep breath. She turned to me with a sad smile. “I feel like my mom totally just sent her in here to tell me all of that.”

We smiled at Beth, still motionless on the hospital bed between us. “She sure did,” I said. “I wouldn’t put it past her.”

The rest of the day passed with conversations standing or sitting at Beth’s side and in the family waiting room across the hall. Joe was exhausted after more than a week of near-sleepless nights, and I volunteered to stay on the small couch in her room. I made a group text message and tested it. “I’ll stay in touch if anything changes,” I promised as they said their goodbyes and filed down the hallway.

The night nurse came in and received his shift report from Amanda. He spent an hour with Beth, checking the pumps, the lines, the levels, the machines. He carefully coiled and arranged every line. I watched from the couch.

“My sister is so happy right now,” I told Nate. “She loves things just so and I know she is noticing the care you're taking with all of these pumps and medicines. She attended to every detail, too.”

“This is what I love to do,” he said. We talked a bit more.

Fatigue crept into my awareness and I felt the draw of the couch. I reached for the pillow and a blanket thrown over the back. “Is there a way to dim the lights?”

“Oh, yes,” he said. “As soon as I am done here, I’ll turn them down and bring you another pillow and blanket so you can get some sleep.”

When he left the room, I leaned over Beth and whispered in her ear. “I’m going to sleep right over there,” I told her. “Just wake me up if you need to go.”

I curled up on the hard couch, and fell into a deep dreamless sleep. An insistent finger poked my upper arm. I sat up to find a young south Asian man pulling a chair in close to sit next to me.

“I’m sorry to wake you,” he said. “I’m sorry that we haven’t met before and that this is the first I’m meeting your sister and reading her case.” He looked at me intently.

“It’s okay,” I said. “I’m awake. I expected it.”

“I’m sorry to tell you, but your sister’s body is actively dying.”

“I know.”

He laid out three options.

“The last one sounds right to me but I’m not the one making decisions,” I said.

He left to call Joe and I sent a series of texts to those who had left just two hours earlier.

They could add a fourth drug to support blood pressure to get her through the night. We could keep her where she is and hope she makes it to morning. The third option is to switch to comfort care after everyone is here.

Regardless of the option chosen, the doctor recommended that we have everyone here earlier in the morning rather than later.

Or, we could all gather now and begin only comfort care. He anticipates that her body will die quite quickly without the meds and ventilator.

Joe’s sister, Mary, texted back immediately: I am on my way in ten minutes.

Olivia texted too: We are leaving soon as well.

Time slowed down. What took only minutes seemed like hours. Everyone arrived and checked through security. We waited in the hallway while they removed the ventilation tube, and then we stood around her bed in the quiet room without the whirring of machines and clicking monitors. We took turns at her head, talking to her softly. We whispered, “I love you. It’s okay to go.” We held hands, massaged her feet.

It wasn’t long, twenty or thirty minutes. She breathed at the same rate as with the ventilator.

Nate came in again. “I am switching off the pressors.”

She took a few more breaths as easily as she had been breathing. Then her face showed the tiniest hint of strain, a wrinkle above her upper lip as she inhaled. "It’s okay," we told her.

I sent her silent messages. I love you. It’s okay to let go. Love never dies. We’re with you.

She exhaled again into a longer pause. Is this the end?

One more breath and she was gone. My brother Peter cried beside me, “Oh, no. Oh. No.”

I checked the clock: 11:44 PM.

Peter cried louder and I turned to hold him.

“It’s okay,” I said. “It’s okay.”

“It’s not okay,” he wailed. “We lost our sister.”

She didn’t feel lost to me.

I held him tight. The clock caught my eye.

The minute hand circled round and round. Each time it passed twelve, the hour hand clicked forward. “Look at the clock,” I said. We all turned and watched.

“What?”

“Oh, my god!”

It kept going and going, hours passing in seconds.

“Oh, come on,” Olivia almost laughed. “Now she’s just showing off.”

As the clock approached seven-thirty, the minute hand slowed.

“Is it going to stop?” someone asked.

It slowed again. The minute hand ticked like a second hand and came to a stop at exactly 8:00.

“What?”

It paused for a few seconds and started again. Then clicked into place at the actual time just before midnight.

“What just happened?”

“Wasn’t she born at eight o’clock?”

“Maybe the hospital is resetting their clocks.”

“That would be some coincidence, wouldn’t it?”

Beth loved the imagery of flying, loved the liminal space between waking and sleeping, She studied lucid dreaming and sailed among the stars most nights. “I flew around the earth last night,” she told me more than once. “We live on a beautiful planet.” She appreciated big and little things. Noticed simple pleasures: sunlight filtering through leaves, birds flitting in the wind, a perfect fall day, daylight breaking on new snowfall.

The magic soaked in.

She’s playing with time, I thought. Beth was showing us that time is just a human construct.

Beginnings, endings, they’re all the same. Eight on its side is infinity.

Her body stopped working, but she goes on.

She’s with the stars now.

About the Author

Linda Castronovo lives and writes in western Massachusetts, land of the Nipmuc and Pocumtuck People. She makes her home with her husband, a yellow lab, a black cat, and a dozen chickens on a tiny hobby farm with fruit trees, berry bushes, and too many weeds. She carries on the work of Starry Starry Kite with her sister's assistance, now in different form.